Unter der Erde WoO VII/6

for voice and piano

-

Unter der Erde

Text: Karl Swiedack

- -

- -

- -

1.

| Reger-Werkausgabe | Bd. II/1: Lieder I, S. 146–187. |

| Herausgeber | Alexander Becker, Christopher Grafschmidt, Stefan König, Stefanie Steiner-Grage. |

| Verlag | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart; Verlagsnummer: CV 52.808. |

| Erscheinungsdatum | Juni 2017. |

| Notensatz | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. |

| Copyright | 2017 by Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart and Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe – CV 52.808. Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. |

| ISMN | M-007-17140-7. |

| ISBN | 978-3-89948-268-3. |

Unter der Erde

Karl Swiedack: Der Mensch soll nicht stolz sein, in:

Franz von Suppé: Sammlung der Neuesten Lieder und Theater-Gesänge mit Begleitung des Piano-Forte v. Franz von Suppé, Capellmeister, Haslinger, Wien

unknown

Used for comparison purposes in RWA: Karl Swiedack: Der Mensch soll nicht stolz sein, in:

Sammlung der Neuesten Lieder und Theater-Gesänge. mit Begleitung des Piano-Forte von Franz v. Suppé, Capellmeister, [spätere Titelauflage der Erstausgabe von 1848], Tobias Haslinger´s Witwe und Sohn, Wien

Copy shown in RWA: DE, Karlsruhe, Max-Reger-Institut/Elsa-Reger-Stiftung.

Note: Regers Textvorlage ist nicht bekannt. Ob Reger den Text im Zusammenhang mit Suppés Vertonung kennen lernte oder ihn allein etwa in einer Zeitschrift fand, ist nicht überliefert. Für die RWA zu Vergleichszwecken herangezogen wurde eine zeitgenössische Titelauflage (um 1880) der Erstausgabe.

Note: Der von Reger gewählte Titel “Unter der Erde” bezieht sich nicht auf ein einzelnes Gedicht, sondern auf den Titel von Elmars dreiaktigem Charakterbild mit Gesang Unter der Erde, oder: Freiheit und Arbeit, das von Franz von Suppé mit Musik umrahmt wurde (Uraufführung 1848 in Wien). Der Text “Der Mensch soll nicht stolz sein auf Glück und auf Geld” findet sich im 2. Akt, 13. Szene, und ist dort bereits als Lied (des Bergwerkaufsehers Hanns Bierschrott) angelegt.

Note: Reger unterlegt seiner als Strophenlied angelegten Komposition nur den Text der ersten Strophe, macht jedoch in einem der zwei erhaltenen Autographe Angaben zur Gestaltung des Übergangs in die zweite und dritte Strophe (s. o., Quelle A6). Der Text dieser beiden Strophen wurde nachträglich unterhalb des Notentexts – vermutlich von Adalbert Lindner – hinzugefügt.

Note: In beiden Autographen Regers (sowie auch in der Abschrift Josef Regers) findet sich eine fehlerhafte Angabe des Textdichters: “Timar” statt “Elmar”.

1. Composition of WoO VII/1–13

Reger, who ultimately became one of the major contributors to the genre in his time with around 300 songs, received his first impetus to focus on composing songs from his future composition teacher Hugo Riemann. Riemann had assessed Reger’s first compositions (see Biographical context) and advised him for the time being “to write songs, chamber pieces, quartet movements, especially Adagios (without variations), in order to learn to think of something longer that motifs of four bars”. Furthermore, he suggested “not to think too much of the upbeat and rather to invent melodies instead of motifs”.(Letter from Hugo Riemann dated 26 November 1888 to Adalbert Lindner)

Reger followed this recommendation, but with some hesitation. Only in autumn of the following year, when he put himself through an intensive training program in music theory as preparation for studying music, did he turn to composing songs: “I will follow your kindly advice to write songs, and will try my hand in this genre one day as well. The first attempt will probably not turn out particularly well”. (Letter dated 28 September 1889 to Hugo Riemann) On 23 November he reported to Riemann the completion of an orchestral work (Heroide WoO I/2) as well as two songs. (Letter) The latter were probably Die braune Heide starrt mich an WoO VII/1 and Winterlied WoO VII/2.1 The setting of Die braune Heide starrt mich an to a text by Wilhelm Osterwald was, according to Lindner, in response to “a request from his mother, a great lover of our German poetry”. Reger received the text for Winterlied from Lindner himself, who had in turn taken it from the Sechs Gesänge op. 19[a] by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy.2 By the end of the year there were already “several songs”, as Reger reported to August Grau, a cousin of his mother Philomena and a professor in Vienna, who was to “sing or whistle them beautifully” on a visit to Weiden. (Letter dated 28 December 1889)

During his studies, a continuing preoccupation with the genre of song remained an important part of his compositional training, with the study of the genre receiving more attention than completing individual works. In his letters to Weiden, Reger only referred to his creative work in this area sporadically or in general. So Lindner heard on 16 November 1890 of a premiere of a Reger song which had taken place that day, probably to a private audience, given by Riemann’s wife Elisabeth, who wanted to “practice further songs and perform them in public in a Conservatoire concert”. (Letter) Reger also counted “a few songs” amongst his new publications, which he brought to Lindner’s attention at the end of that year. (Letter dated 23 to 25 December 1890) According to information from Philomena Reger, at this point “only 2 or 3” of the songs were to be found at the Weiden family home. She sent one of these to August Grau in Vienna as evidence of her son’s compositional progress, probably using one of the copies prepared by Josef Reger around that time. (Letter dated 30 December 1890) On 3 March 1891 Reger referred to a series of songs for the first time, but which were still not intended for public performance: “Otherwise there is nothing new to report; apart from the fact that my songs are now at my parents’ and you should look at them some time. Actually I would not agree to them being sung; they are not yet sufficiently serene, sufficiently idealized for that. That is my present foremost aim[,] to sort everything out[,] not to allow myself to be influenced by modern octave rattling.” (Letter to Adalbert Lindner) In Weiden the songs were “constantly praised […] particularly by father and often sung to close friends”.3 The setting of Mit sanften Flügeln senkt die Nacht WoO WoO VII/3, particularly popular in the family, was apparently arranged as a duet by Josef Reger;4 however, this version has not survived.

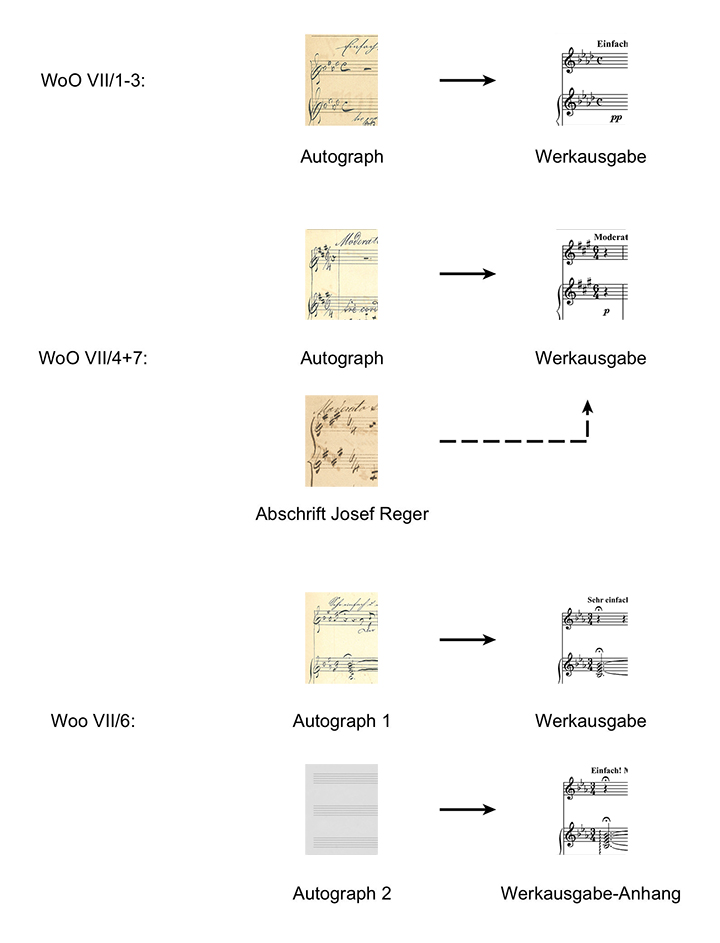

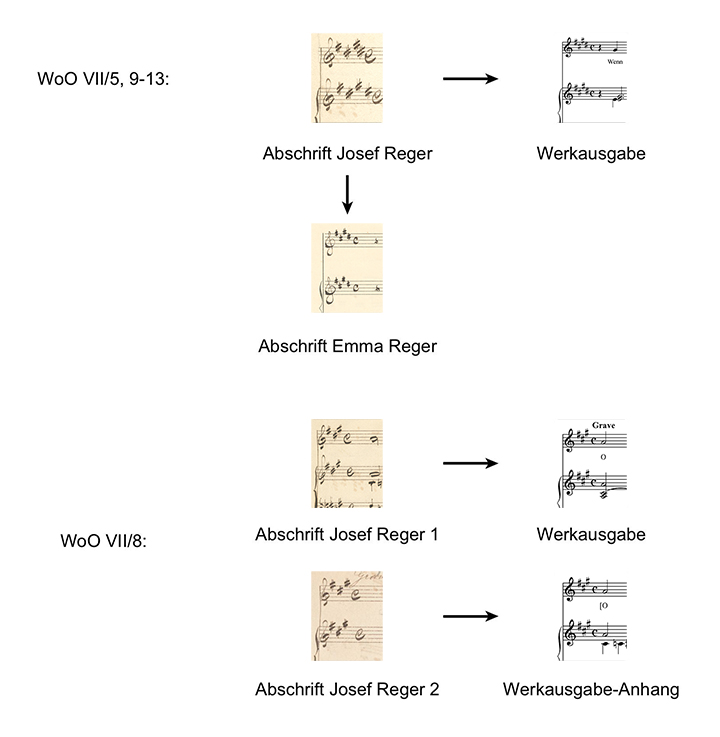

It is not known how many songs Reger composed in total between the end of 1889 and 1891 (Lindner presumed “some twenty” 5). Sources document 13 songs which can be grouped together as “Jugendlieder” (“youthful songs”). However, autograph manuscripts only exist for four of these (WoO VII/3, VII/4, 6, 7)6; for two further songs (WoO VII/1 and 2) the autograph manuscripts survive as microfilms at least. Seven songs (WoO VII/5 and 8–13) could only be edited based on copies made by Reger’s father Josef, and on copies of these made by his sister Emma Reger.

None of the surviving sources is dated. There is a record of the dates of composition for at least the Songs WoO VII/1–12 in two copies of the song texts by Philomena Reger.7

The songs WoO VII/1–13 must be regarded as compositional attempts during his studies with Hugo Riemann and in that sense were “work in progress”. The boundary between revising and rejecting or recomposing a song may have been fluid from time to time. The surviving sources represent, as it were, an accidental selection from the original works, and therefore also represent different stages of the compositional process (see Quellenbewertung). For these reasons, the songs are included in the Appendix, rather than the main part of this volume.

Philomena Reger’s copies of the song texts also contain the poem Vergangen, versunken, verklungen by Peter Cornelius, with the date “c. 1891” (WoO VII/15)). Beyond that there is no further information about the setting. For the Four Songs op. 23 Reger (again) drew on this text.

2.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

1. Reception

At present, there are no records of performances in Reger's time.

1. Quellenbewertung

Der Edition liegen als Leitquellen die Autographen Regers zugrunde, die sich für sechs Lieder erhalten haben (WoO VII/1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7). Im Falle der übrigen Lieder wurde ersatzweise auf die Abschriften Josef Regers als Leitquellen zurückgegriffen (WoO VII/5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Bei Liedern, von denen sowohl Autographen als auch Abschriften Josef Regers vorhanden sind, wurden Letztere als zusätzliche Quellen herangezogen (WoO VII/4, 6, 7). Da sich die Abschriften insbesondere hinsichtlich ihrer satztechnischen Faktur von den Autographen unterscheiden (vgl. Zur Edition der »Jugendlieder«), wurde bei ihrer Berücksichtigung für editorische Fragestellungen besonders zurückhaltend verfahren.

Von den Liedern WoO VII/6 und 8 liegen jeweils zwei gleichwertige Quellen vor: im ersten Fall zwei Autographen, im letzteren zwei Abschriften Josef Regers. Die Quellen repräsentieren jeweils zwei unterschiedliche, jedoch gleichermaßen verbindliche bzw. unverbindliche Stadien im Kompositionsprozess, deren chronologische Abfolge unklar ist. Diese kompositorischen Stadien wurden daher getrennt ediert. Im Falle von WoO VII/6 wurde die Edition nach der Sammelhandschrift »Drei Lieder«, die auch WoO VII/4 und 7 als Leitquelle dient, in den gedruckten Anhang aufgenommen; die Edition nach dem zweiten Autograph ist auf der DVD als PDF-Datei zur Verfügung gestellt. Im Falle von WoO VII/8 erscheint die Edition nach Josef Regers Sammelhandschrift, die auch Abschriften von WoO VII/4, 7 und 9 integriert, im gedruckten Anhang; die Edition nach der ohne Text überlieferten Abschrift findet sich als PDF auf der DVD.

Die nach Regers Tod angefertigten Abschriften Emma Regers (WoO VII/4–13), die wiederum Josef Regers Abschriften zur Vorlage hatten, sind nur für die Überlieferungsgeschichte von Bedeutung1, für die Edition besaßen sie keinen Quellenstatus. Als hilfreich erwiesen sich jedoch dort vorgenommene Korrekturen, die im Falle von WoO VII/10–12 auf ein Verlagslektorat zurückgehen. Die ebenfalls nach Regers Tod erstellte Abschrift des WoO VII/5 von unbekannter Hand besitzt für die Edition keine Relevanz.

2.

3.

4.

5. Sources

Object reference

Max Reger: Unter der Erde WoO VII/6, in: Reger-Werkausgabe, www.reger-werkausgabe.de/mri_work_00982.html, version 3.1.4, 11th April 2025.

Information

This is an object entry from the RWA encyclopaedia. Links and references to other objects within the encyclopaedia are currently not all active. These will be successively activated.