Ten Pieces op. 69

for organ

- No. 1 Präludium e-Moll

- No. 2 Fuge e-Moll

- No. 3 Basso ostinato e-Moll

- No. 4 Moment musical D-Dur

- No. 5 Capriccio d-Moll

- No. 6 Toccata D-Dur

- No. 7 Fuge D-Dur

- No. 8 Romanze g-Moll

- No. 9 Präludium a-Moll

- No. 10 Fuge a-Moll

Heft 1: Herrn Otto Becker zugeeignet.«; Heft 2: Herrn Walter Fischer zugeeignet.

- -

- -

- -

1.

| Reger-Werkausgabe | Bd. I/6: Orgelstücke II, S. 84–132. |

| Herausgeber | Alexander Becker, Christopher Grafschmidt, Stefan König, Stefanie Steiner-Grage. |

| Verlag | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart; Verlagsnummer: CV 52.806. |

| Erscheinungsdatum | Oktober 2014. |

| Notensatz | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. |

| Copyright | 2014 by Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart and Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe – CV 52.806. Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. |

| ISMN | M-007-14353-4. |

| ISBN | 978-3-89948-211-9. |

1. Composition

1.1.

The Ten Pieces op. 69 were written in late 1902 for the Leipzig publisher Hug & Co.. Apart from these ten organ pieces, Reger had also promised the publisher a projected Pedalschule for organ (RWV Anhang-B10), written jointly with Karl Straube.1 Nothing is known about the precise circumstances of the agreement; in view of the intermediary role played by Hug managing director Karl Peiser in the composition of op. 59 and his close links with C.F. Peters, it can be assumed that the success of the Twelve Pieces op. 59 and their continuation in the Twelve Pieces op. 65 in spring 1902 gave the impetus to henceforward include Reger’s organ works in the Hug & Co. publishing programme.

In mid-September the publisher enquired about the progress of the Pedalschule, which Reger had only promised for 1903.2 His expectation of receiving “600 M from Hug at the beginning of November”, mentioned to his fiancée Elsa von Bercken a little later (letter), probably refers to his op. 69. Nevertheless Reger evidently postponed the composition until after his wedding on 25 October and the following move. The Ten Pieces were first specifically mentioned on 21 November 1902 to their dedicatees Otto Becker and Walter Fischer. Reger wrote to Fischer on this date that he had “10 organ pieces in progress now, which will appear in 2 volumes of 20 pages and which I will dedicate to my two Berlin “Apostles”, that is, to you and Herr Otto Becker!” (Letter; see postcard to Becker)

Contrary to his expectation of being able to send the Ten Pieces to Hug & Co. in December (see letter dated 19 December to Lauterbach & Kuhn), completing the engraver’s copy was delayed until the second week of January 1903. On 10 January Reger posted the manuscript.

2. Publication

2.1.

On 10 January 1903 Reger send the engraver’s copy of the Ten Pieces as registered business letter to Hug & Co. 3 A few days earlier his new main publisher Lauterbach & Kuhn had expressed interest in the Pedalschule also promised to Hug. In order to wrest this from Hug, when sending op. 69 Reger firstly deliberately demanded an excessive royalty and thus provoked “a return of my manuscript […]; I received my op. 69 back from Hug today without a letter” (letter dated 13 January; see letter dated 8 January). He took the rejection of op. 69 without comment as an excuse to retract his promise of the Pedalschule.4 On 13 January Lauterbach & Kuhn therefore received the Ten Pieces op. 69, with the desired Pedalschule in prospect. As a royalty Reger again stipulated the modest sum of 600 Marks (letter) which he had requested in spring from Hug & Co. (see Composition).

Reger may have received the copyright agreement for op. 69 after a meeting with Max Kuhn which took place on 1 February in Munich. On 8 February he sent the signed document to Leipzig (letter), together with the exclusive contract, discussion of which had dominated correspondence with the publisher in the preceding weeks (see Biographical context).

In the meantime, Lauterbach & Kuhn had evidently handed the engraver’s copy of the work to Karl Straube to evaluate.5 It may have been given to the engraver immediately after receiving the copyright agreement, for as early as 4 March, Straube performed, probably from proof copies,6 no. 3 Basso ostinato and no. 8 Romanze in his third inaugural concert as the new organist of St Thomas’s, which was exclusively devoted to works by Reger.7 On 19 March the proofs were with Reger (letter), which he took with him on 8 April on his Easter holidays in Berchtesgaden (letter). In the meantime deeply engrossed in work on the Gesang der Verklärten op. 71, he was only able to deal with the proofs gradually and return them on 2 May (letter). He confirmed receipt of the first printed edition on 24 June 1903 and expressed his thanks for the “superb presentation” (postcard).

It is striking that the tempo markings in the first printed edition differ fundamentally in places from the autograph markings in the engraver’s copy (the same applies to the dynamic scheme at the end of no. 3 Basso ostinato). On the publisher’s instructions the engravers initially omitted the tempi, so that the final designations could be entered onto the proofs.8 Evidently Straube had come to the view when playing through the pieces that the autograph instructions were not entirely ideal, for no. 2 Fugue contains a counter-suggestion in his handwriting. The two friends probably discussed possible alterations on Reger’s visits to Leipzig.9 Straube may have made specific suggestions in the process, but undoubtedly the markings in the first printed edition were ultimately revised and authorised by Reger (see Vortragsangaben).

3.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

1. Reception

Reviewers, including several organists, greeted the publication of op. 69 almost entirely positively; a few were unreservedly enthusiastic.

Georg Stolz came to the conclusion that “in these new pieces the best is to be found […] which Reger has written to date. The composer showed his restraint in every direction in these new pieces, so that people’s complaints, including some very ill-considered ones […] were finally silenced.” (Rezension)1

The assessment repeatedly heard was that, in comparison with his earlier boldness, Reger found himself “gradually in his sorting out phase” (A.W. Gottschlag, Rezension) and that it in these pieces, what demanded admiration was “not the composer, but the creator of atmosphere in Reger” (K. Straube, Rezension). Even Walter Niemann stressed that Reger had succeeded best in those pieces “in which he is able to indulge in such melancholy, heavy or meditative moods, particularly in the wonderfully beautiful and deeply-felt “Moment musical” at the end, or in the sensuous, deeply melancholic Romanze” ” (Rezension).

Whilst Moment musical and Romanze were unanimously praised, the unwieldy Basso ostinato divided opinions. Niemann rejected this and the Capriccio as ““almost unbearable pieces”. By contrast, Walter Fischer admitted that the Basso ostinato constantly drew him back “with magic power”, on closer appreciation a “brilliant contrapuntal study which was off-putting at first glance” (Rezension). Roderich von Mojsisovic praised as “almost astonishing the way the composer is able to lend such a wealth of variety […] to the dry, very monotonous bass line which recurs no fewer than nineteen times”.”(Rezension).

Niemann then also described Reger’s technical ability as ““astonishing” and “truly eminent”: “Reger, the greatest contemporary […] organ composer in Germany in no way disowns the old foundation of this Brahmsian-north German school, the elaborate contrapuntal form based on J.S. Bach, and the powerful, immense pull of these works!” (Rezension) His objection that Reger generally inclined towards “heaping up rhythmic complications of the most difficult and futile kind, especially in the middle parts,” conflicts with Robert Frenzel’sobservation of a “multi-voiced lightness which lends Reger’s harmony that shimmering and brilliance such as we only find in Richard Strauß amongst the modern composers”(Rezension).

2.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

1. Stemma

2. Quellenbewertung

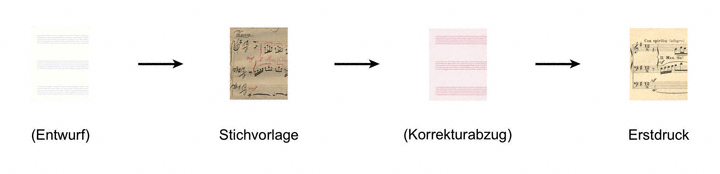

Der Edition liegt als Leitquelle der Erstdruck zugrunde. Als zusätzliche Quelle wurde die autographe Stichvorlage herangezogen.

3. Sources

Object reference

Max Reger: Ten Pieces op. 69, in: Reger-Werkausgabe, www.reger-werkausgabe.de/mri_work_00069.html, version 3.1.1, 31st January 2025.

Information

This is an object entry from the RWA encyclopaedia. Links and references to other objects within the encyclopaedia are currently not all active. These will be successively activated.