Monologe op. 63

Twelve Pieces for organ

- No. 1 Präludium c-Moll

- No. 2 Fuge C-Dur

- No. 3 Canzone g-Moll

- No. 4 Capriccio a-Moll

- No. 5 Introduction

- No. 6 Passacaglia f-Moll

- No. 7 Ave Maria!

- No. 8 Fantasie C-Dur

- No. 9 Toccata e-Moll

- No. 10 Fuge e-Moll

- No. 11 Canon D-Dur

- No. 12 Scherzo d-Moll

Heft 1: Herrn Prof. Dr. Hermann Dettmer zugeeignet«; Heft 2: Herrn Robert Frenzel zugeeignet«; Heft 3: Herrn Richard Jung zugeeignet

- -

- -

- -

1.

| Reger-Werkausgabe | Bd. I/5: Orgelstücke I, S. 118–203. |

| Herausgeber | Alexander Becker, Christopher Grafschmidt, Stefan König, Stefanie Steiner-Grage. |

| Verlag | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart; Verlagsnummer: CV 52.805. |

| Erscheinungsdatum | Februar 2014. |

| Notensatz | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. |

| Copyright | 2014 by Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart and Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe – CV 52.805. Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. |

| ISMN | M-007-14293-3. |

| ISBN | 978-3-89948-206-5. |

1. Composition

1.1.

Through an introduction from the organist and reviewer Alexander Wilhelm Gottschalg, in August 1901 Reger came in contact with Constantin Sander, the owner of the publisher F.E.C. Leuckart in Leipzig. Sander firstly asked Reger for “an organ work” (letter to Gottschalg), but soon after, seemed to be interested in a more long-term collaboration. Thus Reger wrote to Adalbert Lindner on 21 October: “Leuckhardt would like to have a number of things – I can help him.” (Letter) After moving to Munich at the beginning of September and immediately throwing himself into musical life there, Reger firstly wrote the II. Sonata in D minor op. 60 in November/December for Leuckart, and in addition, announced to Lindner at the beginning of December “shorter pieces à la op 59” (letter).

The compositional process itself is not documented, and only on 22 April 1902, as the completion of writing out a fair copy of the work was imminent, was a collection mentioned for the first time: “op 63 ‘Monologe’1 12 Pieces for Organ (56 pages) go to the publisher Leuckart in 8 days.” (Postcard to Theodor Kroyer) Reger submitted the manuscript on 29 April.2

2. Publication

2.1.

On 11 June 1902 Reger informed Hermann Dettmer that he was just working on the printers’ proofs of the first volume, which was dedicated to him: “[…] now I’m searching for mistakes in the engraving”. (Postcard) A week later he was able to inform his future wife Elsa von Bercken: “Thank God I have dealt with all my proofs – but it won’t last long – then even more will arrive! O my darling, it’s a terrible task! It’s completely soul-destroying; 8 hours in succession – you feel totally exhausted! And despite this, I am sure that some misprints will remain!” (Letter dated 18 June)3

To Reger’s evident surprise, as the correction process for the work was not yet complete, on 23 June he received a second set of proofs from the publisher.4 On 30 June, after working on these, he again confided in his fiancée Elsa Reger: “Why I had to go through the proofs again – because there were so many mistakes in the first proofs – and then a second set had to be made! I myself have already dealt with these & returned them!” (Letter) From these second proofs, a double-sided high quality proof copy was also made, possibly for an organist friend,5 from which the sheets of the third volume have survived.

In mid-August the Monologe were announced as a new publication (see Verlagsankündigung) and on 10 September Reger had to confess to Walter Fischer that he had no more author’s copies (see letter). Yet the sales figures do not seem to have satisfied the publisher. Reger reported to Karl Straube about this on 8 December: “Sander (Leuckart), who has been described to me by others as a real ‘skinflint’, wrote one of those cards of complaint to me again today, saying that the demand for op. 60 & 63 is constantly on the decline!” (Letter) The publishing relationship came to a standstill as a result, and was only revived for a short period in 1907/08 with the Two Sacred Songs op. 105.

3.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

1. Reception

Reger’s suggestion of again publishing “shorter pieces à la op 59” with the Monologe (letter to Adalbert Lindner), was gratefully seized upon by the publisher F.E.C. Leuckart as part of their marketing strategy. The publisher’s brochure of September 1902 contained the following information about this new collection: “These twelve pieces, each of which reveals a self-contained atmospheric picture of intense strength, present no great demands on the player’s technique. For a first introduction to Reger’s powerful art, his Monologe are therefore more suitable than almost any of his other works, and for that reason are especially welcome and recommendable.” With this, expectations were naturally raised which Opus 63, in all its parts, could not fulfil, as it contains a few distinctly virtuoso pieces. Reger himself admitted at this time: “I never release anything until I myself have tried it out in practice” (letter to C.F. Peters). On the other hand, he confessed that he had “lost any sense of complexity or degree of difficulty” (letter to Gustav Beckmann). At any rate, the composer countered the complaints of Constantin Sander, the owner of the publishing house, in both fighting spirit (“[…] these are only things […], so that the likes of us feel really small and never dare to ask for anything decent in the way of royalties!”; letter to Karl Straube), and with trust in the future (“It would indeed be a grievous blow if I returned to the old, well-trodden path! Then I would be a one-day wonder. But I want to become more than this”; letter to Sander).

One pair of works in particular, in the same key, became established in the concert repertoire, the Introduction and Passacaglia in F minor from the second volume (nos. 5 and 6); they also received significant interpretations. When they were performed in 1905 in a recital given by the former Straube pupil Fritz Stein, Hans Deinhardt wrote in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik: “Herr Stein introduced Reger’s difficult F minor Passacaglia in Heidelberg, a piece whose force shakes, whose out and out tragedy makes for fear and trembling: it is a song of resignation.” Furthermore, he even described the work as a “tone poem”.1 (Review) Two years later, in his study on Reger and Straube, the philologist Gustav Robert-Tornow enthused about the topos of the sublime, and with reference to the Passacaglia reasoned: “It is as if a person has met his fate and his fate has met him. […] In general, the thought – perhaps utopian? – probably crosses the mind that this organ piece is waiting for a second version; a version for organ and orchestra.” 2

2.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

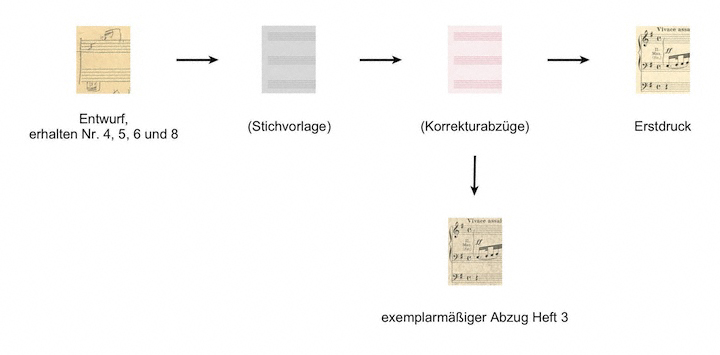

1. Stemma

2.

Der Edition liegt als Leitquelle der Erstdruck zugrunde. Da die autographe Stichvorlage verschollen ist, konnte als weitere Quelle nur der exemplarmäßige Abzug von Heft 3 herangezogen werden, der vermutlich den Stand der noch nicht korrigierten zweiten Korrekturfahne wiedergibt. Deren Abweichungen vom Erstdruck, die Regers Korrekturen indirekt dokumentieren, wurden im Lesartenverzeichnis vermerkt. Die Entwürfe spielten für die Edition keine Rolle.

3. Sources

Object reference

Max Reger: Monologe op. 63, in: Reger-Werkausgabe, www.reger-werkausgabe.de/mri_work_00063.html, version 3.1.4, 11th April 2025.

Information

This is an object entry from the RWA encyclopaedia. Links and references to other objects within the encyclopaedia are currently not all active. These will be successively activated.