Die Nonnen op. 112

for mixed voice choir and orchestra

-

Die Nonnen

Text: Martin Boelitz

- -

- -

- -

1.

| Reger-Werkausgabe | Bd. II/11: Chorwerke mit Klavierbegleitung, S. 136–164. |

| Herausgeber | Christopher Grafschmidt, Claudia Seidl. Unter Mitarbeit von Knud Breyer und Stefan König. |

| Verlag | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart; Verlagsnummer: CV 52.818. |

| Erscheinungsdatum | September 2022. |

| Notensatz | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. |

| Copyright | 2022 by Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart and Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe – CV 52.818. Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. |

| ISMN | M-007-29723-7. |

| ISBN | 978-3-89948-433-5. |

Die Nonnen

Martin Boelitz: Die Nonnen, in:

id.: Frohe Ernte. Noch einmal Verse, J. C. C. Bruns‘ Verlag, Minden i. W.

[Probably] First edition

Copy shown in RWA: unknown

Note: Die Ausgabe befand sich in Regers Besitz.

1. Composition and Publication

In spring 1901 Reger planned a large choral work with the Wesel poet Martin Boelitz, to whom he had been introduced by his friend Karl Straube: “Now to the matter of the “Christusoratorium” with Herr Boelitz! I would want to do something like that; but the text would have to give me the opportunity for grandiose tone-paintings e.g. the death of Christ etc. etc. I will correspond with Herr B. himself about this! Besides, there is a lack of really good texts for a secular choral work of large dimensions! […] the main thing is the dramatic climaxes; only not so lyrically wide-spun” (letter dated 7 May to Karl Straube). The plan for the oratorio was probably discarded, but Boelitz presumably still sent him his poem Die Nonnen possibly written for this purpose in May. Reger took the liberty of suggesting alterations: “I like the poetry enormously – I only ask for two things to be altered urgently: “Hundert helle Glocken etc.” [a hundred bright bells]. It seems more atmospheric to me if the bells are not “hell” [bright], but have a more “traumhaft verschleierten” [dreamlike, veiled] sound, and the word “Hundert” [hundred]! As an opening word, such a “brutal austere” concept – “hundred”, which invites jokes far too readily – is not suitable for composing! I ask you most sincerely not to resent this suggested alteration; it only springs from my great interest in your poetry! Think of such a Tristan-like, transcendental, religious sensual mood – this cannot begin with a hundred!” (Letter dated 8 June 1901)

But the version revised by Boelitz did not meet with Reger’s approval either:

[…] forgive my openness: the alteration does not match the original; firstly “dumpfe Feierglocken” [dull celebration bells], secondly “junge Mädchenlippen” [young girls’ lips]! I would say: “junge Seelen” [young souls], which is distinctly more suitable than “young girls’ lips”! And now don’t laugh when I, who have never written a single verse in my life, and will also never compile one, allow myself to suggest an alteration in the first verse to you:

“Wehmutsweiche Glocken” schwingen [“Wistful bells” swing]

Durch den kühlen Tempelhain [Through the cool temple grove]

Heiße, “junge Seelen” singen: [Ardent, “young souls” sing:]

In die stille Nacht hinein. [Into the still night.]

You see, this way more of the first wonderful version, which I greatly admire, would be preserved […]! Ask yourself and see whether you agree with this change of mine.

(Letter)1 Finally the passages in question would read: “Helle Silberglocken” [bright silver bells] and “junge heiße Seelen” [young, ardent souls]. A copy of the poem in its final version, but not in Boelitz’s hand and with a few comments by Reger,2 was found in Adalbert Lindner’s papers;3 he may have retained the folio (together with various manuscripts) when Reger moved from Weiden to Munich on 1 September 1901.

Reger must have owned another copy of the poem, which was first published in 1905 in the collection Frohe Ernte, since at the end of 1903 “a marvellous text by Martin Boelitz: “Die Nonnen” for choir and orchestra!” (Letter dated 3 December to Josef Hofmiller) must have figured amongst his as yet unrealized plans. And Fritz Stein finally reported, the “mystic-Catholic text by his friend M. Boelitz” had “already inspired Reger in the last Munich summer [1906] to musical sketches”,4 but these have not survived.5

In spring 1909 Reger turned once more to Straube for help: “I have many new composition plans! Please, find me a text for a choral work (with orchestra) of 30 minutes duration!” (Postcard dated 17 March) He even involved the publisher C.F. Peters: “It’s true, isn’t it, Herr Ollendorff is surely kind enough to look for a text for a choral work (without soloists) for mixed choir and orchestra of 25 minutes duration! Please, talk to him about it!” (Letter dated 4 April 1909 to Henri Hinrichsen) On 5 April he sent the Heidelberg University Music Director Philipp Wolfrum a text: “[…] I will compose this for mixed choir, orchestra, & then dedicate the whole thing to you. Hopefully you will agree with this!” (Letter) As the copy of the text has not survived, it cannot be said with certainty whether this was already Die Nonnen, especially since Reger only presented Straube with his final decision three weeks later, as if it were news: “I have a wonderful text for a choral work – highly peculiar! Entirely new in mood! It is by Boelitz!” (Postcard dated 27 April) And just about a month later he also informed the publisher Bote & Bock: “The new choral work I wrote to you about,6 which you will still receive in 1909, has a very peculiar text; it is an atmospheric picture such as we have not yet had in the whole of choral literature! It is a text of quite wonderful poetry – “Die jungen Nonnen” [The young nuns]!” (Letter dated 23 Mai)

Hugo Bock was pleased “that you have chosen such a beautiful text for our choral work” (letter dated 24 May), and received not only the poem from Reger on 28 May, but also heard about his ideas for the work he had not yet started on: “But I am not going to compose the “Gesang der Nonnen” in that “Liedertafel style” with which Strauss portrayed the prophet Johannaan in “Salome”! In contrast to the mystic-sensual mood of the rest of the poem, the Song of the Nuns will be in a consciously very old style, such as, for example, in an old church mode in the style of the 14th–15th century, which will and must give the work a very distinctive charm! I will only compose this twice iterated Song of the Nuns for women’s choir and only with accompaniment for violas (these divided!) […] and through this accompaniment a very austere “innocent” sound will be achieved which must contrast enormously from the sound color of the other verses. A really great intensification can be achieved at the words: “Sieh, und aus dem goldnen Rahmen tritt der Heiland nun herfür” [See, now from the golden framework steps the Saviour down below]! The conclusion then in the highest transfiguration!” (Letter dated 28 May)

On 13 June Reger outlined his time scale to Hugo Bock: “You will definitely receive the new choral work “Die Nonnen” at the end of this year. […] on 9 August I am going to Colberg on the Baltic for 6 weeks […]. There I am going to diligently bathe in the sea and work. The “fruit” of this summer holiday will then be the “Nonnen”; but I will then need a good 2 months to get the score into a final, finished state.” (Letter)

After he had sent the engraver’s copy of the Motette “Mein Odem ist schwach” op. 110 no. 1 to the publisher on 9 July, Reger seems to have found the time and leisure to turn to the composition, as he reported to Bock on 12 July: “It will no doubt interest you to hear that I have already begun on the choral work “Die Nonnen”, the text of which you are familiar with; the introduction is almost finished!” (Letter) On 20 July he was “already steadily at it, but it is a real “slog”” (letter to Hugo Bock). Two days later the “1st verse [was] finished; the poem has 3 verses, it will be a very peculiar thing” (postcard dated 22 July to Karl Straube). On 26 July Reger was “in severe birth pangs with the Nonnen! Please, just interpret this figuratively, otherwise it would be too immoral” (letter to Hugo Bock). To put it more precisely, “the 1st half [was] already written out in score” (letter to Adolf Wach). On 28 July the Nonnen were becoming “fatter and fatter i.e. the score” (letter to Hugo Bock), and on 5 August Reger promised the publisher: “You will definitely receive the score & piano reduction of the choral work “Die Nonnen” at the end of September a.c. [annus currens = current year] at the latest!” (Letter to Gustav Bock) and the same day added the date of completion at the end of the engraver’s copy. Straube and the dedicatee Philipp Wolfrum learned of the completion of the work before Reger’s departure on holiday.7

Despite having added the date of completion to the engraver’s copy, Reger continued to “work a great deal on the “Nonnen” in Kolberg. There will be a “rush” when the work is performed!” (Letter dated 12 August to Hugo Bock) Here he must still have been involved with the “black” musical text, since on 22 August he wrote to Gustav Bock: “The score of “Die Nonnen” is ready & waiting; now I still need to add the performance instructions and do the piano reduction! By roughly 1 October at the latest you will receive the score!” (Letter)8 By 27 August at the latest the “red” layer of performance instructions was probably complete: “I am now also preparing the piano reduction of the choral work “Die Nonnen”! It is best if I do the piano reduction myself!” (Letter to Gustav Bock) He expected to be finished with this work “in the next few days”. “The work must go to print straight away[,] from 7 September onwards the score and piano reduction will be available for you!” (Letter dated 28 August to Gustav Bock)

With regard to the layout of the score Reger had specific ideas which he wanted to discuss personally with the publisher in Kolberg.9 The meeting did not take place because Gustav Bocks was ill, so that Reger sent the score and piano reduction (as well as two other, shorter works)10 to Berlin “with a lengthy letter which contained everything worth mentioning” (postcard dated 7 September to Gustav Bock). With regard to the Nonnen this was mainly concerned with the layout of the score.11 As early as 16 September Reger sent a reminder about the proofs of the piano reduction,12 and at the end of October made the urgency all the clearer: “When finally will I receive the proofs of the “Nonnen” for the piano reduction and score? It is very, very urgent, since they want to start rehearsing the work in Dortmund where the first performance takes place at the Reger Festival in May 1910. Please ensure that I receive these proofs as soon as possible; you have already had the work longer than 6 weeks!” (Letter dated 29 October to Hugo Bock) After repeated enquiries13 Reger expressed his thanks on 23 November for the proofs received and promised “to deal with everything as soon as possible” (letter).

He evidently took the proofs of the score with him to Straube, to whom he wrote on 27 November, two days before his departure to concerts including in Munich, asking: “On 7 Dec. in the evening I must have the proofs of the “Nonnen” back!” (Postcard) On the same day he promised Hugo Bock: “You will then definitely receive the corrections of the piano reduction of “Nonnen” on 13 December.14 As very little is needed, the piano reduction and choral parts of this work can comfortably be published on 1 January! […] I will then deal with the proofs of the orchestral parts during the Christmas holidays; you will then definitely still receive these proofs before 1 January, therefore the score orchestral parts can be there mid-February!”” (Letter) On 8 December he had to press Straube: “I must immediately have the corrections of the score of the “Nonnen”!” (Postcard)15 On 12 December he had completed proof-reading the piano reduction16 and promised Bock shortly before the turn of the year: “You will receive the corrections of the proofs of the score of the “Nonnen” at the very latest on 4 January, that is the final date; I have checked through the score with the greatest care, have a look through it again and again.” (Letter) The direct comparison with the engraver’s copy had already been completed by this point, as Reger had sent this to the dedicatee Philipp Wolfrum on 28 December;17 the publisher received the proofs on the promised date18.

Reger received the first printed edition of the piano reduction by 30 December at the latest, and immediately sent a copy to Wolfrum.19 The score must have been published at the beginning of February,20 as Wolfrum thanked him on 8 February with a slight delay (“I was on my travels for 2 days, otherwise I would have written straight away.”) for “kindly sending it and the dedication” (Wolfrum’s letter to Reger). Similarly, a registered printed document to Martin Boelitz listed for 11 February 1910 in the Postbuch 3 may possibly have contained a copy of the first printed edition.

2.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

1. Early reception

For the first performance on 8 May 1910 at the Dortmund Reger Festival under Julius Janssen, Herman Roth provided an introduction to the new work printed in the program booklet. In his understanding, Reger was attracted by the “neo-Romantic-religious mood of longing which was the order of the day in poetry of the 1890s” represented through the poem: “he expands it, deepens it, gives it a personal momentum which elevates it far above what the […] coincidentally poetic model originally contains […]. […] BOELITZ’s poem offers the most direct inducement to strike similar notes of mystical devotion and dedication [as in Psalm 100 op. 106], and indeed in the closest connection with specifically Catholic ecclesiastical ideas: REGER’S religious sensitivity can be traced back here to its original state; an external musical analogy for this process can be seen in the fact that the composition displays multiple truly striking echoes of “Parsifal” within the framework of REGER’s particular nature, the work which at its time led the fourteen-year-old [recte: fifteen-year-old] to discover the productive force within himself.”

The critics of the first performance reacted consistently positively to a “choral work […] rich in musical beauties and luminous images […]. With which moving harmonic sequences the “Liebeszagen” [hesitations of love] is portrayed, how enthralling the “ängstige Klagen einer sterbenden Braut” [terrified lamentations of a dying bride]!” (Dortmunder Zeitung) Eugene Simpson found “not a minute wasted. The composition is highly charged with some beautiful spirit, almost as of modern opera” (The Musical Courier), for Arnold Spanke “a romantic, poetic magic [lay] over the choral writing as over the orchestral sections” (Tremonia), and Walter Paetow counted the Nonnen “amongst Reger’s most mature works. Choir and orchestra have equally impressive stories to tell of the nuns’ suffering and renunciation. One is tempted, from the moving sounds which are heard here, to infer a symbolism for the everlasting sacrifice and longing of woman which can never be fulfilled. Mystic-ecclesiastical sounds mingle with those of real life and make one think of a faith which is born out of doubt.” (Tägliche Rundschau) Hermann Wilhelm Draber, on the other hand, noted “a barrenness probably caused by the text of the otherwise opulent thematic material in Reger’s work” and saw in this a “move towards simplicity” (Hamburger Nachrichten).

In other reviews up to 1913 too (there are no records of later performances during Reger’s lifetime), the sensuousness of sound of the Nonnen was repeatedly emphasized: Karl Werner praised the “strikingly well-conceived sound of the work” (Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung), and the otherwise critical Clemens Droste nevertheless heard “atmospheric music of the most skilful texture and rich in interesting effects in orchestration and harmonisation” (Rheinische Musik- und Theater-Zeitung), and the reviewer of the Sammler detected: “Enchanting magnificent tone colour in the orchestra, choral writing no less glowing, filled with the hot breath of a strong temperament” (review).

The stylistic simplification already hinted at was also favorably received: for Richard Specht “Reger’s work was quite different from his previous, without his spiky rhythmic polyphony, less “pointillist”, painted with a broad brush in glowing colors, at its high point (“und aus seinem goldenen Rahmen tritt der Herr” [and out of its golden frame steps the master]) filled with glowing beauty of sound and rich, lush brilliance” (Die Musik). The Osnabrücker Volkszeitung concluded: “Anyone who has not yet really been able to come to terms with Reger will certainly have come a few steps closer to him upon hearing this work.” (Review)

However, Reger’s interpretation of the text was perceived as problematic. For Rudolf Louis “the actual weakness of the work [appeared to lie] in the relationship of the music to the poetry. It is not as if Reger had not excellently captured the moods of the (incidentally poetically rather bad) poem by Martin Boelitz […]. But it is embarrassing that Reger has allowed himself to be tempted to portray all the intensification of the poem, which is, so to speak, only an inner intensification, purely externally-dynamically through increasing the volume of sound, instead of striving for an intensification of the expression of sentiment. So, in the music, the “Liebeszagen” becomes a wild raging, the anxious sound of longing becomes a wild screaming, and in more than one place the noise becomes so bad that it could hardly be worse if the poem were to tell of the wildest excesses.” (Münchner Neueste Nachrichten) To the reviewer of the Sammler the composition “in all its passionate beauty [seemed] too opulent, too sensuous for the tender soul-eroticism of the poem” (review).

Reger’s orchestration was identified as one of the causes: “Certainly, everything sounds good with him as he applies everything very strongly and mainly employs all the instruments. But he does not yet possess the secret of how to give the orchestra “color” to the extent that we are used to with other modern composers.” (Bonner Konzert- und Theater-Zeitung) Although Arthur Hahn acknowledged the “present richness of Reger’s orchestral palette of colors […] […] with the best will in the world, one cannot say that this powerful outpouring of means and ability and the whole character of this musical language matches that of the poem and the special art of its purely psychological events.” (Münchener Zeitung)

Furthermore, many reviewers wrote criticially – Herman Roth had already done so in the Dortmund program booklet – about what they perceived as the “rather dilettante” source (Eugen Schmitz, in Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung), “impossible to take seriously” (Alfred Heuß, in Leipziger Zeitung), occasionally also with reference to “Reger’s lack of literary culture” (Hamburger Nachrichten), and Alfred Heuß combined this with the verdict: “Reger’s literary taste is indeed absolutely dreadful, one of the reasons why Reger will never be seriously considered as a song composer and is already of little interest today.” (Leipziger Zeitung) The reviewer of the Heidelberger Tageblatt therefore summarized: “If it were true that bad texts are more suitable for setting than good […], then Reger’s work could be a classical masterpiece; for he has chosen a very unsympathetic text this time. This turgid schoolboy lyric, this fervency of banality is simply unbearable. But I cannot agree that Reger has succeeded in constructing a temple over this swamp.” (Rezension)

And whilst some enthused about the “monumental composition […] with its unified but gigantic part-writing” (Heidelberger Zeitung), others regarded it “as entirely intellectually misguided and a motley stylistic collage as a whole” (Hamburger Nachrichten). Alfred Heuß: “One cannot get away from the feeling of lack of any recognizable style, arising in particular from the fact that some sections seem unmistakably dramatic, whilst the starting point is lyrical in nature. Also the fact that Reger works with impressionistic means, has high notes vibrating for minutes at a time and the like, is also unpleasantly surprising, because such things actually do not fit with Reger at all; it is a foreign drop in his blood. Also the kind of sensuousness, the moaning and lamenting, does not seem particularly sympathetic with Reger, it is not really that original, and one does better to go straight to the modern source, to works by Richard Strauß.” (Leipziger Zeitung)

2.

Translation by Elizabeth Robinson.

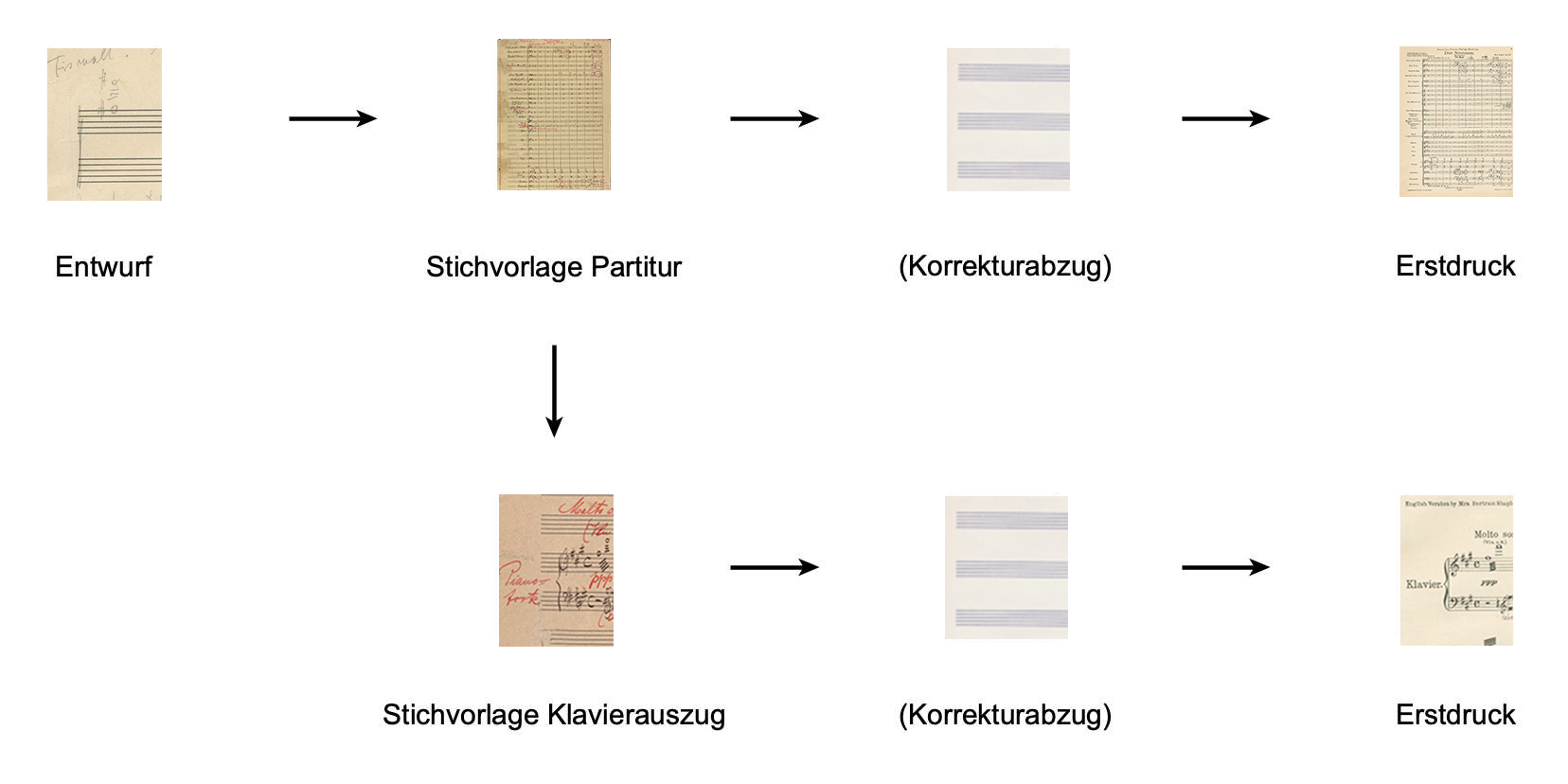

1. Stemma

2. Quellenbewertung

Aufgrund der Bestimmung des Klavierauszugs als Hilfsmittel zur Einstudierung des Werks liegt der Edition als Leitquelle für die Gesangsstimmen sowie für die allgemeingültigen Tempoangaben der Erstdruck der Orchesterpartitur zugrunde, für die Klavierstimme der Erstdruck des Klavierauszugs; punktuell fehlende dynamische Angaben oder Artikulationszeichen u.Ä. in Vor-, Zwischen- und Nachspielen des Klaviers werden entsprechend der Umgebung ohne diakritische Auszeichnung nach der Orchesterpartitur ergänzt.

Als Referenzquellen wurden die Stichvorlagen der Orchesterpartitur und des Klavierauszugs herangezogen; der Entwurf spielte für die Edition keine Rolle.

Es ist denkbar, dass Reger bei der Erstellung des Klavierauszugs oder der Bearbeitung von dessen Korrekturabzug manche Stellen im Chor bewusst oder unbewusst anders auszeichnete als in der Orchesterpartitur bzw. gar den Notentext änderte, diese bedeutungstragenden Abweichungen jedoch nicht durch Nachtrag in der Orchesterpartitur für das Werk an sich legitimierte.

3. Sources

- Entwurf

- Stichvorlage der Partitur

- Stichvorlage des Klavierauszugs

- Erstdruck der Partitur

- Erstdruck des Klavierauszugs

Object reference

Max Reger: Die Nonnen op. 112, in: Reger-Werkausgabe, www.reger-werkausgabe.de/mri_work_00137.html, version 3.1.1, 31st January 2025.

Information

This is an object entry from the RWA encyclopaedia. Links and references to other objects within the encyclopaedia are currently not all active. These will be successively activated.